Florence Price

Americaʻs Rediscovered Symphonic Pioneer

The first Black woman recognized as a symphonic composer in America, Florence Price wrote music rooted in both classical traditiona and the spiritual rhythm of her heritage. Her voice, once overlooked, now resounds with the dignity and depth that she always deserved.

In 2009, a couple renovating a long-abandoned house in St. Anne, Illinois, found a pile of papers scattered across the warped wooden floor. Rain had leaked through the roof, the piano was gone, and time had nearly erased the traces of whoever had once lived there. On several of the tattered pages, a single name appeared in careful, looping script: Florence Price.

The manuscripts were damaged, some beyond repair, but their meaning was unmistakable. They contained the music of a woman who had broken barriers no one else had crossed, then slipped quietly out of history. No one knew, at that moment, that the voice sealed inside those pages was about to be heard again.

The find electrified the classical music world. Scholars and performers realized they were looking at the near-complete works of the first African American woman to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra. It was as though a voice silenced by history had suddenly begun to sing again.

The rediscovery didn’t just unearth lost manuscripts; it reignited an entire conversation about who gets remembered in classical music, and who gets erased. Florence Price had broken through barriers of race and gender that once seemed immovable, only to vanish from concert programs for more than half a century. Now, with each recovered score and performance, her music is reclaiming the place it always deserved.

Roots and Early Brilliance

Florence Beatrice Smith was born in 1887 in Little Rock, Arkansas, into a family that seemed to have all the ingredients for success in a world that rarely allowed Black excellence to flourish. Her father, Dr. James H. Smith, was Little Rock’s only Black dentist. His practice was interracial, serving both Black and white patients, including the governor of Arkansas. Her mother, Florence Irene Smith, was a trained pianist, a former schoolteacher, and a businesswoman who held positions such as secretary of the International Loan and Trust Company.

The Smith home was part of what W. E. B. Du Bois described as the “Talented Tenth,” the educated professional class of African Americans who sought to uplift their race through intellect, refinement, and culture. Their home was filled with books, conversation, and music. Because public libraries were closed to Black residents, the family kept a formal library of their own. The Smiths often hosted prominent guests, including Frederick Douglass and the poet Langston Hughes, and young Florence grew up surrounded by the energy of social progress and artistic ambition.

Her mother taught her piano when she was about three or four years old, and Florence gave her first recital by age four. By eleven, she had reportedly published her first composition. Music was so much a part of her identity that one childhood sketch found among her papers featured a girl at a piano, captioned simply: “MY CAREER.”

Her talent came naturally, but her discipline came from her mother. Florence was a brilliant student, graduating as her high school valedictorian at just fourteen. The family’s social standing and her mother’s fierce guidance opened the door to opportunities rarely available to Black children in the South, including the chance to study at one of the most prestigious conservatories in the country.

Yet, even in this promising beginning, the shape of her future was already forming: a life of brilliance hemmed in by the limits of race and gender, and a determination to create her own space within those boundaries.

Becoming the Composer: Education and Reinvention

At fourteen, Florence left Little Rock to attend the prestigious New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, one of the few institutions in the early 1900’s where a Black woman could even dream of formal training in classical music. Her admission was not guaranteed, and her mother knew it. Fearful that racia prejudice might bar her daughter from opportunity, she advised Florence to register as a student from Pueblo, Mexico, allowing her to pass as Latina and sidestep some of the discrimination she would otherwise face.

That single decision said everything about the world Florence was entering. To be safe enough to learn, she had to hide who she was. Yet the irony of her story is that this period of concealment gave rise to one of the most authentically American musical voices ever to emerge.

At the Conservatory, Florence was both a prodigy and a workhorse. She completed a double major in organ and piano pedagogy in only three years, a program that normally took four. She studied composition and counterpoint under George Whitefield Chadwick, a composer who had been a champion of using American folk music as the foundation for serious concert works. Following the ideas of Antonín Dvořák, Chadwick encouraged students to look inward to the musical idioms of their own land for inspiration.

Florence absorbed this lesson deeply. Her own “folk” tradition was the music of African Americans: spirituals, work songs, and the rhythmic dances that pulsed through Southern Black life. She would later say that this heritage was not a curiosity or an influence, but a “rich resource for the creation of uniquely American concert music.”

Her time in Boston was transformative. She learned to master the European forms – symphonies, concertos, sonatas – that had defined “serious” composition for centuries. But she also began to imagine what might happen if she filled those forms with the sounds she had known since childhood: the sway of a spiritual, the syncopation of a Juba dance, the bittersweet tonalities of gospel and blues.

When she graduated in 1906, Florence returned to the South as a rare phenomenon: a Black woman with an elite musical education, prepared to build a professional career in a world that still refused to see her as equal. Her next chapters would test every ounce of her resilience and ingenuity.

A Composer in Exile: Racism, Resilience, and the Great Migration

When Florence returned to Little Rock after graduating from the New England Conservatory, she arrived with impeccable credentials and the confidence of a woman ready to build a career. What she found instead was a wall of exclusion. The Arkansas State Music Teachers Association refused to admit her because of her race, despite her superior training and her proven teaching abilities.

Price responded the only way she knew how. She founded the Little Rock Club of Musicians, a professional circle for Black performers and teachers who had also been shut out of white institutions. She taught music in segregated schools, organized student recitals, and wrote new works for her own community to perform. Through sheer determination, she created the very professional environment she had been denied.

Meanwhile, however, the world around her was growing more dangerous. The South in the 1920’s was tightening its grip on Jim Crow segregations. A lynching occurred near hear husband’s dental office, and the family began receiving threats, including one against their youngest daughter. The violence made it clear that talent and respectability would not protect them.

In 1927, Florence and her family packed their belongings and joined the Great Migration, moving north to Chicago in search of safety and opportunity. Chicago offered a different kind of challenge: fierce competition and a fast-paced city life. But there was also a vibrant Black cultural renaissance. The city’s South Side was alive with writers, painters, and musicians building new spaces for artistic freedom.

There, Florence began again. She took advanced composition courses and began to build strong ties within Chicago’s network of Black composers and performers through organizations that provided vital stages for musicians barred from major concert halls. She began to find a community there that valued her skill and vision, and that same energy which had once driven her to found her own club in Little Rock now fueled her in Chicago, where she could finally be both composer and collaborator.

Her flight from Arkansas was more than a geographic relocation. It was a turning point in her evolution from talented musician to artist with purpose. The move forced her to transform displacement into expression and personal loss into artistic identity.

The Chicago Years: Finding Her Voice

Chicago gave Florence Price what the South never could: room to breathe and a stage from which she would be heard. The city was alive with creative momentum, its air charged with jazz, poetry, and the echoes of newly found freedom. Black artists, writers, and musicians were redefining what American culture could be. Florence arrived at the heart of it, armed with a conservatory education and an unshakable drive to make her mark.

In Chicago, where Florence Price composed her most celebrated works, a neighborhood school now bears her name — a quiet reminder that her music endures.

Photo: Ralph0411, 2019.

CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Returning to her study of composition, she began to refine her craft and experiment with new harmonic ideas. But more importantly, she found a network of allies and fellow visionaries though the Chicago Music Association and the National Association of Negro Musicians, organizations that existed precisely because major institutions excluded Black performers and composers. These groups provided venues, competitions, and performance opportunities for musicians like Price to share their work with supportive audiences who understood both their brilliance and their struggle.

In 1932, Florence entered the Rodman Wanamaker Music Competition, a national contest designed to spotlight African American composers. She submitted her Symphony No. 1 in E Minor, a sweeping work that combined European symphonic form with the melodies and rhythms of Black folk traditions. Her piece won first prize.

The victory led to a milestone moment in 1933, when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed her symphony during the World’s Fair. It was the first time a major American orchestra had ever performed a work by an African American woman. The audience and critics alike recognized the historical weight of the occasion. The Chicago Daily News wrote of her performance, “It is a faultless work … a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion. Miss Price’s symphony is worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertory.”

Her success was celebrated not only as a personal triumph but as a symbol of collective progress. The writer Shirley Graham Du Bois captured the national significance when she wrote in 1936, “Among her millions of citizens, America can boast of but a few symphonists. And one of these symphonists is a woman – Florence B. Price.” (02)

Even as her reputation grew, Florence’s daily life remained far from glamorous. Divorced and raising two children, she juggled composing with the demands of teaching and financial survival. She wrote popular songs and teaching materials under the pseudonym Vee Jay, since those pieces sold better than her classical works. (02) She also continued to write sophisticated piano compositions for advanced players, many of which revealed her playful and lyrical touch.

Despite these struggles, Chicago became for her the landscape of artistic self-discovery. Her experiences there crystallized her musical voice: formal yet free, dignified yet deeply human. She had learned to balance the discipline of European tradition with the emotional depth of her heritage, creating a sound that was both distinctly American and uniquely her own.

Her Music: A Symphony of Two Worlds

Florence Price’s music lives at the meeting point between the concert hall and the cotton field. She spoke both musical languages fluently and refused to choose between them. Her education gave her mastery of European forms like the symphony, sonata, and concerto, but her heart belonged to the sounds of the Black South: the spirituals, work songs, and dances that carried centuries of memory. The fusion of those traditions became her signature voice, what scholars later called the Afro-Romantic style.

Her belief was simple and radical at the same time. She wrote that Black musical idioms were “rich resources for the creation of a body of uniquely American concert music.” That conviction guided her through everything she composed.

The Architecture of Emotion

In Price’s music, classical discipline meets emotional storytelling. Her orchestration is lush but never ornamental, her melodies lyrical yet grounded in rhythm. Listen closely, and you’ll hear call-and-response patterns echoing through her instrumental lines, a hallmark of African American musical tradition. The violins may “speak,” and the cellos may “answer.” She uses syncopation, the subtle shifting of rhythm that makes a phrase sway instead of march. Even her slow movements seem to breathe with human cadence rather than mechanical precision.

Symphony No. 1 in E Minor

This is the piece that made history. When the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed it in 1933, Florence Price became the first African American woman to have her work played by a major orchestra. The four-movement symphony is structured within the European classical mold, but its soul is unmistakably American.

The most famous section, the third movement, is marked “Juba Dance.” The Juba was a lively folk dance with roots in West African and Caribbean traditions, performed through rhythmic clapping and foot-stomping known as “patting.” Price translated that energy into orchestral language, using layered percussion and syncopated strings to capture the feel of communal rhythm. It’s joyful, earthy, and unmistakably hers.

The premiere of her Symphony No. 1 in E Minor was more than a milestone for representation; it was a triumph of craft. Contemporary reviewers praised the symphony’s balance of emotional depth and formal control, noting that Price’s work stood confidently beside that of her peers. The performance proved that her artistry was not an exception to be admired out of novelty, but an achievement worthy of the American orchestral tradition.

The Mississippi River Suite

Composed a year later, her Mississippi River Suite (1934) paints a vivid musical journey down the river that shaped so much of American life. It weaves original themes with the melodies of famous Negro spirituals, including Go Down, Moses, Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, and Deep River. These songs surface like memories within the larger symphonic flow, their textures shifting as the river widens. The piece ends on Deep River, not as lament but as release, suggesting a current that carries both sorrow and hope.

Piano Works

For Price, the piano was not only her instrument but her diary. She wrote over two hundred piano pieces that range from concert sonatas to teaching materials for children. (03, 04) Her Sonata in E Minor is often cited as one of her most profound works, full of Romantic grandeur and harmonic daring.

Yet not all of her piano music is solemn. Pieces like Placid Lake and Whim Wham (a term meaning “something done on a whim”) reveal her playful side, full of caprice and spontaneous joy. These lighter works remind us that Florence Price was not only a figure of perseverance but also of delight.

Music for the Next Generation

Price also believed in the accessibility of art. Many of her piano miniatures for children have vivid, story-like titles such as The Froggie and the Rabbit and Golden Corn Tassels. Through them, she connected professional artistry with community teaching, ensuring that young musicians, especially those who looked like her, had music written for them.

A Legacy of Listening

To hear Florence Price today is to hear the conversation between two worlds that once seemed irreconcilable. Her compositions hold tension and tenderness side by side, proving that technical mastery and cultural authenticity are not opposites. They are, in her hands, parts of the same melody.

Politics of Silence: Race, Gender, and the Canon

Florence Price lived and worked in a country that applauded her talent in public and then quietly erased her in private. She understood exactly why. In a 1943 letter to conductor Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, she wrote that she faced “two handicaps: those of sex and race,” and she asked only that her work be judged on merit. The letter was never answered. The Boston Symphony has still never performed her music.

From the beginning, the politics of her existence shaped every aspect of her career. In Little Rock, she had been denied entry to the Arkansas State Music Teachers Association because of her race, even though she was more qualified than many of its members. Later, as a single mother in Chicago, she relied on teaching and publishing piano pieces under a pseudonym to make ends meet, knowing that the world of serious composition was still largely closed to women, and especially to Black women.

Institutional barriers like these did more than restrict her opportunities. They distorted how her achievements were perceived. When Symphony No. 1 in E Minor premiered in 1933, newspapers described her as a “Negro woman composer,” emphasizing her identity before her artistry. The phrasing was meant as a compliment, but it carried the quiet assumption that her race and gender were exceptions to overcome rather than integral parts of her creative voice.

Price rejected that framing in her art. She chose not to mask her heritage but to integrate it into her compositional language. Her use of spirituals, call-and-response phrasing, and rhythmic vitality was not an attempt at novelty. It was an act of reclamation, asserting that the music of her people belonged in the same concert halls that had once excluded her.

Still, those same politics that celebrated her briefly also ensured her disappearance after death. She died in 1953 with hundreds of unpublished manuscripts in her home, many of which were later thought lost. The neglect was not an accident of history; it was the result of a system that recorded and preserved the works of white male composers while allowing others to fade into silence.

Yet even in that silence, her influence endured. Within Black musical circles, her name remained a symbol of what could be achieved in spite of impossible odds. Shirley Graham Du Bois wrote in 1936 that Price stood as proof of “America’s few symphonists,” noting with pride that one of them was a woman. That recognition, while limited, kept her legacy alive long enough for the world to rediscover her.

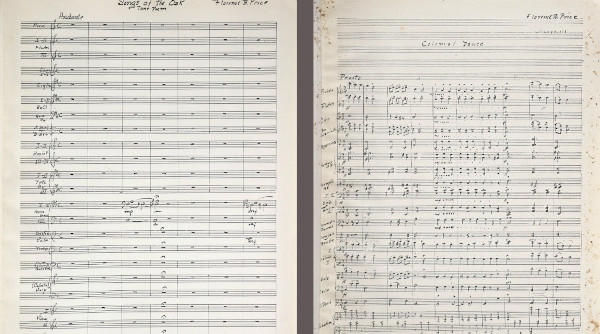

Once forgotten in stacks of unpublished pages, Price’s manuscripts like Songs of the Oak remind us how easily brilliance can be silenced — and how powerful its return can be.

Photo: Manuscript page from Florence Price’s Songs of the Oak (unpublished). Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons

The Rediscovery and Why It Matters

That house in St. Anne, Illinois, turned out to be Florence Price’s summer home. Inside those ruined walls were hundreds of her lost manuscripts: symphonies, concertos, piano works, and choral scores. There were also letters and diary fragments that revealed her thoughts on race, artistry, and belonging.

The find was extraordinary, but what followed was even more important. Archivists at the University of Arkansas cataloged and preserved the collection, allowing scholars and musicians to reassemble scores that had been scattered or incomplete for more than half a century. Composers and performers began to breathe life into her music again: Trevor Weston reconstructed the Concerto in One Movement, describing the process as learning “the essence of a person” through her notes. Violinist Er-Gene Kahng premiered several of her works and reflected that, even across cultures and languages, musicians could meet through “shared training in the same musical language.”

Those revivals sparked a renaissance. Orchestras across the United States began performing her symphonies and suites not as historical curiosities but as vital works of the American repertoire. The Fort Smith Symphony Orchestra has since undertaken the project of recording all four of her symphonies for the Naxos label, ensuring her complete orchestral voice can finally be heard.

For a new generation of musicians, especially young Black composers and performers, the restoration of Price’s music is more than rediscovery. It is validation, and proof that their cultural inheritance belongs at the center of classical art, not its margins. Her story now functions as both history and mentorship, a reminder that brilliance can survive even systemic neglect.

Her lighter piano works like Whim Wham and Placid Lake have also found new audiences. They reveal her humor and humanity, a counterpoint to the constant narrative of endurance. These rediscovered miniatures show that Florence Price was not defined solely by struggle; she was animated by delight.

In 2018, the Arkansas State Music Teachers Association, which had once refused to admit her because of her race, posthumously honored her contributions to music. The gesture was long overdue, yet deeply symbolic. The state that once turned her away now claims her as one of its own.

The Resonance of Florence Price

Florence Price once wrote that Negro music should not be seen as a curiosity, but as “rich resources for the creation of a body of uniquely American concert music.” Her belief has proven prophetic. Decades after her death, her melodies, her rhythms, and her very presence in the concert hall are shaping a broader, more honest understanding of what American classical music truly is.

Her symphonies and concertos now share programs with the great European masters she once studied, and her piano works are being taught to the same young students who might once have been told that composers who looked like her did not exist. Each performance rebalances the story of classical music, turning what was once exclusion into inclusion, and what was once silence into sound.

Florence Price’s life was marked by dualities: privilege and prejudice, success and dismissal, erasure and rediscovery. Yet the arc of her story bends toward restoration. Her work bridges two traditions, European form and African American soul, and in doing so, it gives voice to a fuller vision of America itself.

In rediscovering Florence Price, we are not just recovering lost manuscripts. We are acknowledging that her music was never gone, only unheard. And now that it has been heard again, it is unlikely ever to be silenced.

Sources

Barlow, Harold. Florence Price. University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

(Collected essays and contextual material about her life, originally released with accompanying scores.)

Brown, Rae Linda. The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price. University of Illinois Press, 2020.

(The definitive scholarly biography.)

Capitol Records / G. Schirmer / Naxos. Liner notes from recordings of Florence Price’s orchestral and chamber works, especially the Symphony No. 1 and Piano Concerto.

(Includes notes by Leslie Dunton-Downer, John Jeter, and others.)

Center for Black Music Research (CBMR). Archival material, biographical summaries, and recovered works of Florence Price. Columbia College Chicago.

(The hub for much of the rediscovery of her manuscripts.)

Davis, Christopher A. “The Rediscovery of Florence Price.” American Music Teacher 68, no. 4 (2019).

(A strong overview of the revival and modern reception.)

Gillespie, James E. Notable Black American Women. Detroit: Gale Research, 1992.

(Includes a biographical entry on Price.)

Gillespie, James E. “Florence Price.” In A Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1982.

(A standard reference source for her career and catalogue.)

Grove Music Online. “Price, Florence B.” Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/

(The main encyclopedia entry — updated and reliable.)

Redman, Jessie. “Florence Price and the American Symphony.” Journal of the Society for American Music, 2017.

(On her symphonic style and compositional significance.)

Sowande, Fela. “The Music of Florence Price.” The Black Perspective in Music 5, no. 1 (1977).

(Classic early scholarship on her style and contributions.)

University of Arkansas Libraries. Florence Price Papers (Special Collections).

(The archival home of her manuscripts and rediscovered works.)

Woods, Aminah. “Florence Price: An American Voice.” Smithsonian Magazine, 2018.

(Public-facing article on her rediscovery after manuscript recovery.)